What is Developmental Editing?

You’ve spent months (or years) writing a novel. It’s your magnum opus, your passion project—the product of hundreds of hours and thousands of written words. You love it, you care about it, your grandma thinks it’s amazing, but… you’ve been through it so many times, you don’t know whether it’s a masterpiece or the literary equivalent of a moldy apple destined for the compost heap.

You long to produce something great—a strong, publishable book, but you know, either intuitively or from responses from beta readers, that your story isn’t hitting the mark.

Something isn’t quite right with the plot or the character arc or x or y or z, but what exactly? You’re too close to it to figure it out. Or maybe you know what’s wrong, but don’t know how to fix it. (As a writer, all these scenarios have been true for me at different points in the writing and editing process.)

And as much as you love your grandma and appreciate her enthusiasm, you suspect that her feedback is skewed by her love for you, and by extension, everything you make—no matter how good or bad it is. Case in point: she raved about that chocolate cake with the mysteriously runny batter you baked in sixth grade. Later, you realized you’d forgotten to add flour.

So a worry eats at you: What if you left something crucial out of your book and you haven’t realized it?

You’re tired of endlessly self-editing and second-guessing the changes you make.

You feel lost and frustrated.

You wish you could get professional eyes on your work: Someone who knows the craft and can look at your manuscript objectively to help you figure out not only what is wrong but also suggest potential solutions—all while being kind and supportive.

This is what developmental editing is for.

The Definition

Developmental editing looks at a manuscript from a big-picture viewpoint, considering structure, plot, character development, character arcs, point of view, pacing, tone, and readability. The Editorial Freelance Associate sums up a developmental edit as a critique that considers content, organization, and genre.

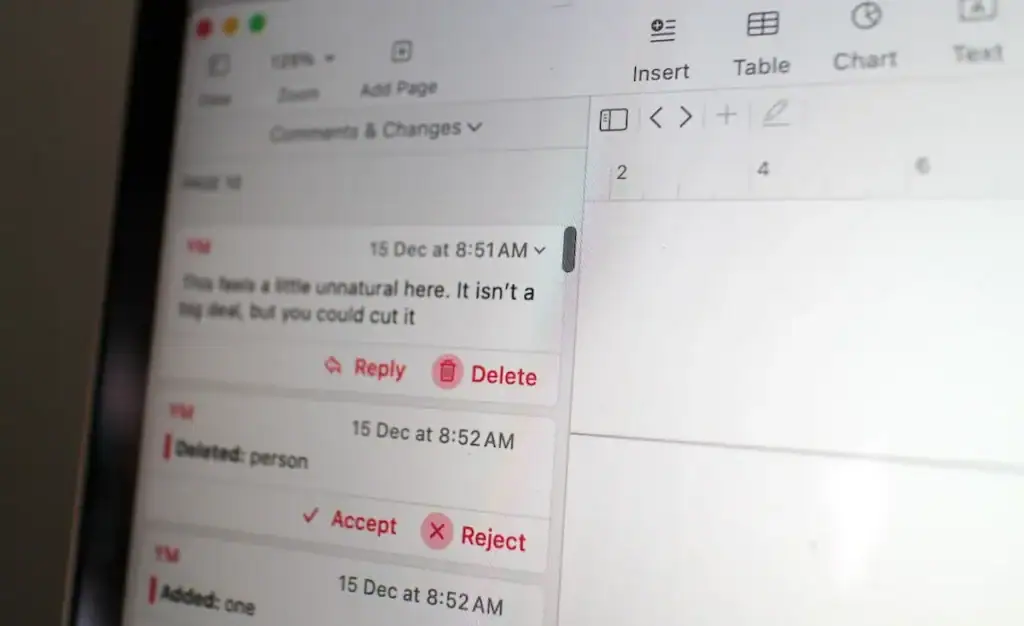

Although different developmental editors work in different ways, most will read through the manuscript, leaving comments, reactions, and questions. Then, they will offer an overall critique, often through an editor letter, explaining the big-picture issues they found and suggesting solutions and strategies for how to address them.

The goal with a developmental edit is to give you clarity. To say: “Here are the main issues I’ve noticed in your book. Here are some ways you might consider to fix them.”

Armed with this information, you can tackle edits with confidence.

Rather than beating aimlessly through the woods, bushwacking and going in circles, you suddenly have a drone-like view of the landscape, a map with directions, and an achievable end-goal.

Will it be easy to get to that goal? Maybe not. But if you persevere, you will get there… or at least a whole lot closer than you would have otherwise.

The Benefits

The feedback I got from my first developmental edit launched me into a nine-years-and-counting quest to understand and improve as a writer. I started reading craft books, researching story structure, evaluating the plots of books and movies, attending summits, and taking writing courses.

There is always something new to learn or try—a different approach, perspective, technique, or consideration. Like the Tardis, the world of writing is always bigger on the inside. There are more rooms to explore, more worlds and times to visit. But we can’t get there all on our own. We need guides, companions, co-adventurers, and Dr. Whos.

A good developmental editor can unlock new and bigger rooms for us. They can help us expand and improve our work, recognize untapped wells of potential, and consider different possibilities for what our story could be so that we can choose the one that best matches our vision. That’s what I look for in a dev edit, and that’s what I aim to provide other writers as a developmental editor. Learn what developmental editing did for me.

Developmental edits are, at their heart, pragmatic. But they also touch on a deeper truth: Just as we put our characters through the fires of adversity to force them to transform, we writers often need to put our manuscripts through the fires of critique to improve the work and to grow in our craft.

I say this as both a writer and a developmental editor. Am I biased? Maybe. But the reason I got into editing is because of the massive difference going through this process made for me as a writer.

Was it painful? The first time was excruciating.

Was it worth it? Absolutely.

Has it made me a better writer? One hundred percent.

Writing can feel lonely. (I know.) Many of us long for someone to root for us, to coach us, to be in our corner and tell us not only that we have stuff to work on, but what we’re already doing great on and how to hang on to those great things while we improve our areas of weakness.

Although getting a dev edit isn’t the same as having a writing coach (though some editors also offer coaching and continued support), it can mean a lot to have that outside perspective. And a good developmental editor should tell you what you do well as well as what you need to work on.

Okay, but how does this kind of editing compare with all the other kinds of editing out there? How does it stack up against a line edit, copyedit, proofread, etc.?

I was confused too, starting out. So, let’s take a quick look at different kinds of editing to help differentiate them.

Types of Book Editing

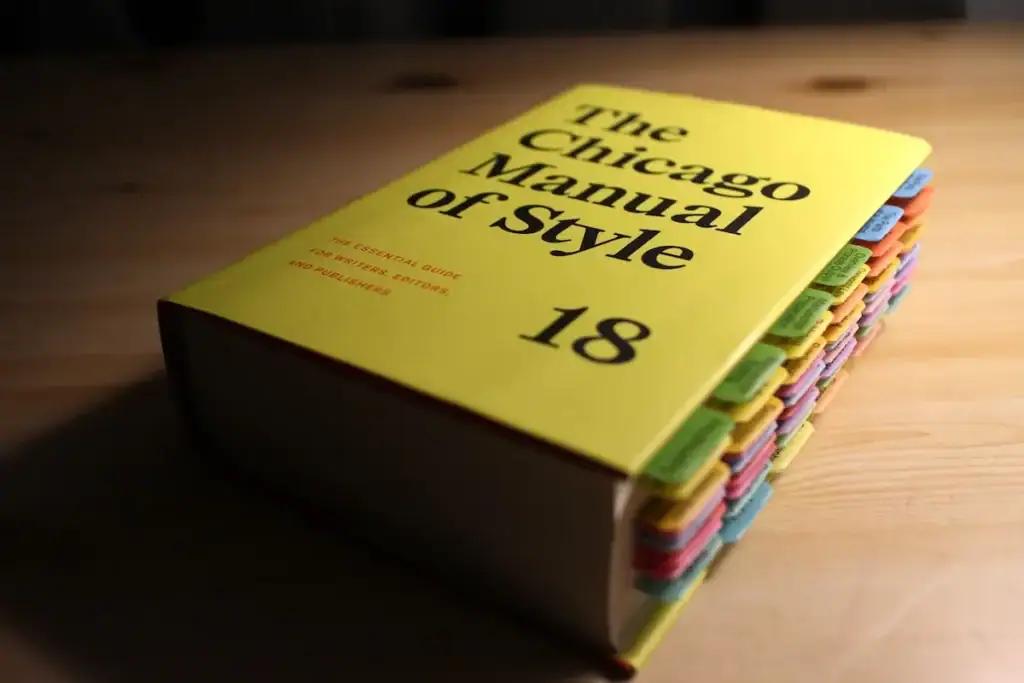

Think of editing as a process of refinement, starting with the biggest picture stuff, and leading down to the details of comma usage.

Developmental Edit: The dev edit comes first, helping you hammer out the story, the character arc, the pacing, all that big picture stuff that you need in place.

Line Edit: Next comes the line edit, which makes your sentences sparkle.

Copyedit: From there, you need a copyedit to make sure the grammar is golden and there are no typos, dangling modifiers, or comma splices.

Proofread: And once all that is dealt with, and your book is in book form (typeset and you have the proof), almost ready to publish, you put it through the proofreading pass to catch any final mistakes, errors, or typos introduced during typesetting.

I think of editing the way I think about sculpting in clay. (Yes, I dabble.)

You start with a lump that vaguely resembles a head. As you go, you scrape and cut, adding here, shaping there. You rough in the features. Then you back off to look at it with a more critical eye, and see what you’ve got.

Maybe you ask your brother for his opinion, and he tells you that the nose is too low and the eyes are too far apart, and the neck may as well belong to a giraffe.

So you fix all that and then you start refining, adding more details: eyebrows, pupils, philtrum, earlobes, clumps of hair.

Finally, you smooth the skin and add texture to the hair. Then, you make sure all the bits of clay are aligned just how you want them, all the nicks have been filled in and smoothed over, and your sculpture is ready to dry and fire.

When to Get a Developmental Edit

There are different approaches to this, but ultimately, I would encourage you to get a developmental edit once you have a complete story that you have self-edited as thoroughly as you can, put your manuscript through at least one round of beta feedback, implemented revisions, and fixed all the errors you can.

The better shape your draft is in, the higher-level feedback your editor can give you.

That said, don’t get stuck in an endless loop of self-editing and beta feedback. You can hire an editor at any stage of the writing process, even before you start writing. (Though in that case, you’re probably looking for a book coach.)

Since a developmental editor can suggest major overhauls, it’s a good idea to get one while you’re still willing to do that kind of work. In other words, if you’re just looking for a pat on the back and a publishing green light, you’re not going to be thrilled when your editor sends you sixteen pages of suggestions for changes you could make.

I’ve had clients come to me wanting a developmental edit and expecting to publish in the following two months. Most have had to put publishing on hold because they needed to make large structural changes. Personally, I think it’s better not to rush. Invest the time that your manuscript deserves.

If you’re a new writer and this is your first book, I would recommend getting a dev edit sooner rather than later. Self-edit and get some feedback, but don’t wait too long because you don’t know what you don’t know.

Take it from me: I waited until I’d been working on my first book for five years, only to discover I needed to go back to the drawing board and learn about story structure. Youch. But hey, better late than never! Looking for an example of a developmental edit? Check out this post.

How Long Does A Dev Edit Take?

It depends on how long your book is and how much other stuff an editor has on their plate, but most take three to six weeks.

I’ve put my young adult fantasy novel through two developmental edits. The first time, my manuscript was just over 70k, and the dev edit took one month. The second time, my manuscript was 95k, and the edit took six weeks.

When to Book an Editor

Although some editors may be able to take your manuscript right away, most need you to book their services one or more months ahead.

So, it’s a good idea to start looking for a developmental editor in advance. That way, you’ll have time to find someone who is a good fit for you, you’ll have time to book the editor in ahead of when you’ll need them, and once you’ve booked one, you’ll have a deadline to work towards.

Extra motivation boost, am I right?

What Kind of Editing Do I Need?

Most of us can majorly benefit from a developmental edit. From there, it depends what you plan to do with your manuscript.

If you’re Indie publishing, I highly recommend a copyedit and proofreading pass.

If you plan to traditionally publish, the stronger your book is and the more polished, the better your chances of getting picked up by a literary agent. So it comes down to time and budget.

When I was querying my young adult fantasy novel, I hired a developmental editor, but did the line editing myself. Then I used ProWritingAid to catch grammar mistakes and typos.

If I choose to Indie publish, I will hire a copy editor and a proofreader. I would do this even if I were a copyeditor. Why? Because all of us develop “word blindness.” We stop seeing mistakes. Our brain auto-corrects for us. There are some ways around this (such as working on a physical copy and listening to your manuscript with text-to-speech tools), but ultimately, I would want another pair of eyes on my book.

If your published book is full of typos and grammatical errors, that is not a good look.

How Much Does Developmental Editing Cost?

Well, there’s a pretty big range. According to the Editorial Freelance Association, developmental editing typically costs 3 to 4 cents per word for fiction (or $50 to $60 per hour) and 4 to 5 cents per word for nonfiction (or $55 to $70 per hour). According to author and writing teacher Suzy Vadori, the true range is between ½ cent and 10 cents per word.

Usually, editors who are starting out in the field charge less. You’ll notice that my developmental editing rates are on the lower end of the Editor Freelance Association’s spectrum. This isn’t because my work is of lower quality, but because I want writers on lower budgets to be able to afford this service.

No matter what, you’ll want to make sure you’re getting the best quality service you can within the limitations of your budget. We’ll talk later about how to choose a developmental editor and make sure they are a good fit, plus red and green flags to watch out for.

Why is it so expensive?

Developmental editing is a very time-consuming process. Beyond that, it requires a lot of brain juice. Trust me. It sucks massive amounts of creative and thinking power.

Every manuscript is different and requires an intelligent, thoughtful, and comprehensive approach. Not only do developmental editors leave in-line and embedded comments, they also write a report outlining key problems and recommending solutions.

I can usually only edit for a few hours a day because after that, I can’t think clearly anymore. I want to make sure I come to the manuscript with my top energy, brain power, and enthusiasm. But I’ll often be thinking about the story even when I’m not directly working on it, considering different aspects of the plot, slowly putting my finger on sneaky issues, and brainstorming solutions.

It isn’t uncommon for me to wake up in the wee hours of the morning, mulling a story over in my head and thinking how best to explain an issue to the writer and what strategies might work for them and their story.

All this to say, it’s a full-on, full-in, involved process!

How to Prepare for a Dev Edit

Self-Editing and Beta Feedback

The better shape your manuscript is in, the higher-level feedback a developmental editor can offer. So if you’re manuscript is pretty rough and you have to go back to the drawing board on the plot, you might need multiple developmental edits.

Ultimately, one way to save money is to self-edit the manuscript as much as you can. It can also be helpful to enlist beta readers and critique partners to read and comment on your manuscript.

I would encourage you to take your manuscript as far as you can—with a caveat. If at any point you get stuck, need that expert advice, or just don’t know how to move on, it could be time to pull the trigger on a developmental edit or work with a book coach.

And if you’re completely new to writing a book, getting critique and direction earlier in the process can help you correct errors and advance more quickly.

Of course, figuring out what to DO with feedback is a whole different story, but I’ve got a post on how to evaluate and implement feedback. It is tailored to developmental edits, but it applies to other kinds of critique as well.

Growth Mindset

Ultimately, it is helpful to go into a developmental edit with a certain mindset—a mixture of rootedness and receptivity.

Giving your manuscript to someone else is scary. It requires bravery to be that vulnerable. It also requires a certain pragmatism: an openness to critique and change alongside a knowledge of who you are as a writer and what you care about and envision for this work.

Getting feedback can be demoralizing, so you also need grit, a spirit of perseverance, a clear reason why you write, and why you’ll keep writing. Learn more crucial mindset tips that will help you prepare for critique.

Okay, But Does it Actually Help?

Now you know what a developmental edit is, about how much it costs, when to get it, and how it compares to other types of editing. But you’re still not sure.

I get it — it’s scary. Every time I’ve sent my manuscript off to an editor, I’ve thought:

Man, that’s a lot of money I could use to visit my sister in Hawaii or go bike-packing with my bro.

What if it isn’t worth it?

What if the editor hates it?

What if their feedback crushes me?

What if they tell me I should’ve listened to my aunt and become a teacher instead?

Those fears are real and worth acknowledging. But when I finally pushed past them, something unexpected happened.

Next up: What developmental editing did for me — and how it changed my book.