Ways to Save on Developmental Editing Costs

Developmental editing is a powerful way to make your book better, but you have bills to pay, groceries to buy, your vehicle needs repair, your dog got sick and had to go to the vet, and you just blew what remained of your budget on a dental emergency. It’s going to take time for you to scrape together enough savings to pay for an editor. And even once you have enough, you want to make sure you get the most bang for your buck. So what do you do?

You do what many thrifty and enterprising writers have done before you: self edit your book, enlist the help of alpha and beta readers, find critique partners and writing groups, get your hands on free/cheap resources, and deepen your knowledge of the craft.

I know what it’s like not to have the budget for this service, and I’ve used each of these methods myself. So, I have lots of tips, suggestions, and warnings to share, complete with concrete examples based on my experiences.

Ultimately, my goal with this post is to show you ways to improve your book and save money on editing costs by:

- Reducing the need to get multiple rounds of professional/paid editing, which can add up fast.

- Making sure you’ll get the highest level feedback for your book once you have the money to invest.

- Giving you the skills, community, and support you need to make the most of your developmental editing feedback.

How These Methods Helped Me

At the point when I finally had a completed draft of my novel, I couldn’t afford a developmental editor. That’s a big reason I try to keep my prices on the reasonable end of the spectrum.

I had just moved into a house that needed major repairs. Then I got sick for nine months and had to pay specialists lots of money to figure out what the heck was wrong with me and how to get better. To top it off, I got a dog that I had to keep fed and vaccinated. (So worth it, she’s a cutie.)

Although I was still making enough from my freelance job to scrape by, I wasn’t what you’d call flush. Meanwhile, the worldwide plague was going on, piling extra suck and complications on top of a difficult situation.

Fortunately, I knew what tools I could turn to in order to improve my book without spending big bucks. (Learn basic info about developmental edits, including rates)

Although I was eventually able to hire a developmental editor, by then my book was in much better shape so I was able to get higher-level editing suggestions. I’d also strengthened my writing and editing skills, which helped me implement the developmental editing feedback to the max.

Did it take longer? Yes. But sometimes, we have more time than money. And the good news is that these skills continue to serve me with each new thing I write.

Here are the techniques I used:

1. Hone Your Self Editing Skills

Some writers love editing and others hate it, but we all have to do it.

I’m solidly in the “love editing” camp, which is handy since I’m more of a pantser than a planner. I stand it awe of people who can outline entire books, trilogies, and even 14-book-series before sitting down to write. Seriously, you guys are brilliant. Hats off!

But one advantage to my approach to writing is that I had to learn to edit. My early drafts were jumbled messes that I trashed and rewrote as vastly different iterations.

Use Self-Editing to Unpack Your Story’s Potential

As a result, I’m not afraid to chuck things out, delete, rearrange, reimagine, make massive structural changes, eliminate characters, and start over from almost scratch. Draft and draft again.

This mindset is one of the most important when it comes to self editing.

An early draft is a mishmashed creature holding pure potential. There are so many directions you could take it. Rather than thinking of your work-in-progress as a thing set in stone, consider it lightly. See what’s in there: all the disparate threads, the gaping plot holes, the half-developed characters.

Like an unfired clay pot, it can be cracked apart, slaked down, returned to a plastic state, and reformed. Something beautiful and unforeseen could result.

That said, as I’ve refined my editing process, I’ve found it helpful to approach my self edits by loosely following these steps:

- I give the manuscript a rest, setting it aside for at least a week before reading the whole thing again.

- During this read-through, I note all the problems I encounter. Some of the problems I won’t know how to fix until I spend time brainstorming, considering, and letting my thoughts incubate.

- I work through the manuscript, making the changes I know how to fix, and brainstorming and sitting with the ones I don’t. I repeat this until I’ve dealt with all the problems, then I get outside critique, and start the process over a few times.

Main Areas of the Story to Self-Edit

I find it helpful to consider each of these areas in turn:

Story Structure: Am I hitting the plot points? Is the story pivoting where it needs to pivot?

Character: Are the plot points a direct result of the character’s decisions? Do they force the protagonist to transform? Is there a clear change in the character from the beginning of the novel to the end?

Stakes: Are the stakes clear throughout the novel? Do they increase as the novel goes on?

Worldbuilding: Is the world developed enough? Can readers picture it? Do I have all of the pieces I need? Are the details compelling?

Interiority: Do we get deep inside the protagonist’s head? Can we feel with the main character? Understand their thoughts, actions, motivations, and fears?

Since I’m more of a pantser and discovery writer, I usually need to sift through the chaos of my early drafts to find the story: identify, rearrange, or reimagine the plot points, sift through my character motivations, determine the arc, and then rearrange, rewrite, and make it clearer.

Often, this is called reverse outlining, and it’s a helpful tool for us pantsers.

Everyone self edits differently, but it’s helpful to keep learning the craft, hearing what other people do, picking and choosing from various people’s methods until you find a revising strategy that’s a good match for you.

Sometimes, having direction and a strategy can make a big difference and make the process feel more manageable and less arbitrary and mysterious.

Resources I’ve Found Helpful When Self-Editing

There are so many it’s hard to pick, but here are a few:

- All of Daniel David Wallace’s courses

- Stacy Juba’s Book-Editing Blueprint self-editing course

- H.R. D’Costa’s resources on stakes

- Heather Davis’s podcast and summit talks on interiority

2. Enlist the Help of Alpha & Beta Readers

Sometimes as writers, we don’t know how things are coming across or even how much of what is in our heads we’ve put on the page. We might think a scene or motivation is clear, or that a particular character is likable. The only way to know for sure is to enlist the help of readers.

If our readers don’t understand our story, if they get bored and start skimming, if they’re confused, then we have more work to do. Our job as writers is to write for our readers.

Now, there are different kinds of readers out there who can help you self edit:

Alpha Readers: These are your earliest readers, the ones who willingly immerse themselves in rougher drafts.

Beta Readers: By the time you enlist beta readers, your story should be more polished and complete. They will help you refine it even more.

How Early Readers Helped Me Self-Edit

Using alpha and beta readers helped me realize I needed to:

- Flesh out my worldbuilding

- Tone down metaphorical language in my book

- Improve the clarity of what was happening in the action sequences

- Be way less mysterious about what and why things were happening

- Refine scenes, character arcs, paragraphs, and sentences

- Understand where I needed to add more foreshadowing

Not only that, one of my readers suggested an idea that dramatically changed the entire plot of my book, helping turn it into a much more high-stakes and dramatic adventure.

Guidelines for Getting Alpha and Beta Feedback

Getting strangers to read your book can be helpful because they won’t come into it with any biases or be afraid to tell you the truth. Although I’ve occasionally paid for a beta reader, most of the time I’ve enlisted the help of family and friends who have kindly read my book for free. You can also find beta readers in writing groups and Facebook groups.

When choosing a beta reader make sure:

1. They read and enjoy the genre of your book

I made a huge mistake early on in letting someone read my book who didn’t read fantasy. But he begged me to let him read it, and I said yes, even though my gut feeling was that it was a bad idea.

This person read the first 20 pages of my novel, completed a word search for the word “death” in the remaining pages, and then wrote me a horrified email expressing concern about my mental, emotional, and spiritual health. He suggested I quit writing fantasy and start writing devotionals.

Even though he meant well, I can’t tell you how painful and damaging it was to get this reaction from a friend. It fed into all my worst fears about sharing my work and resulted in a creative wound that I’m still unpacking years later.

Recently, I read back through my correspondence with this person and realized that he probably had no idea that my book was a fantasy story involving an assassin. That was unfair to both of us. I should never had let him read my book. (Hint: avoiding this kind of situation is one of the benefits of getting feedback from a professional.)

Don’t make my mistakes. Make sure your readers LOVE your genre and are in your ideal audience.

- Tell them the genre and subgenres

- Let them know the basic premise of your story

- List out all potential trigger warnings

For example, if I were looking for beta readers now, the minimum I would say is:

Genre: My book is a young adult fantasy adventure novel

Logline: When the assassin who killed his dad marks him with an unhealable magical wound, a disillusioned teen must rediscover lost mending skills before the magic feasts on his life.

Trigger Warnings: Death of a parent, grief, murder, injury, suicide ideation, physical fighting, blood, burns, epidemic, brief mention of decapitation, brief mention of war. It does not contain sexual content or real-world curses.

These make it sound pretty dark and dire, but it would give readers who have reservations the opportunity to ask additional questions!

Get confirmation that they are not only on board with all of these things but enthused.

Lastly, tell them that if they start reading and discover that this is not the book for them, ask them to simply let you know, no explanations needed.

2. Are willing to give you kind and honest feedback

Creatives are sensitive souls. We put a lot of ourselves into our creative works and our creativity can be easily damaged or blocked. Getting feedback often makes us feel vulnerable. Therefore, it is crucial to find people who are willing to give you constructive criticism. People who lead with curiosity and who are kind and honest.

For example, ask them to tell you not only what confused them but also what they liked and loved about your writing, your characters, the plot.

Ask them to tell you the places where they felt their attention lagging and wanted to (or did) skim, as well as the places where they couldn’t stop reading because they were so sucked in.

DO NOT ask for brutal honesty. I did, and it was a mistake. I was afraid that my book wasn’t good and that no one would tell me. I was afraid I’d end up putting work out there that I’d be ashamed of eventually.

It’s important to acknowledge those fears, but the solution is not brutal honesty from someone who is going to crush your creative spirit. Too often, brutal honesty just ends up being brutal.

The solution is finding people who can be kind as well as honest. (I aim to do this as a developmental editor.)

Consider the following made-up comments. Which ones would you rather get?

1. This sentence is stupid. It makes no sense.

2. I’m not sure what you mean. Can you clarify?

3. I’m interpreting this sentence/scene/reaction this way and this way. Is that what you intended?

3. Can get the book back to you in a reasonable amount of time

My experience with beta readers is that most need 2 to 4 weeks. Some take longer. I once had to wait 4 or 5 months for one of my beta readers. Not ideal!

Let potential readers know what time frame you are looking for. Ask if they can commit to that deadline knowing that it will likely take a few of them longer.

It’s also likely that some of your beta readers won’t finish the book or will forget to tell you when they are done.

My suggestions:

- Ask them to commit to a particular time frame

- Check in with them during that time frame to ask how they are progressing. Don’t be shy!

- Use the check-in to remind them to let you know when they are finished

- Schedule a call with them as soon after they finish reading as you can so that you can get their fresh take before details get fuzzy.

4. Understand the kind of feedback you’re looking for

Another thing you’ll want to tell your alpha and beta readers up front is what kind of feedback you want from them.

Ask them to pay attention to specific things. Tell them how nitpicky you do or don’t want them to get.

For example: Grammar is not my main focus. My main concern is making sure the story works!

Example Email to Beta Readers

Hello Jay, Leslie, and Emma!

Thank you for your willingness to read my novel and give me kind and honest feedback on my novel to help make it better and see how it communicates to readers.

Some guidelines:

Deadline: If at all possible, please try to finish reading within the next 3 weeks. (Approximately February 14th).

Change your mind? If you get a few chapters in and don’t think this story is for you, that’s okay. Just let me know. If you want to, you can still give me feedback on what you read, but no hard feelings either way!

Feedback Guidelines:

If possible, comment with your thoughts or take notes as you read, even if it’s to say, “Ooh, I like this” or to make predictions about what will happen next.

This shows me how people read my book. It also helps me pinpoint where changes need to be made and gives me a feel for how you reacted while reading.

Please look for:

- Areas you felt were missing something or weren’t developed enough

- Sections or scenes superfluous to the story

- Any part of the story, dialogue, or narrative you didn’t understand or found confusing

- The flow and pace of the chapters

- Where possible, supply “whys,” not “shoulds.” For example: “I’m confused here because…” or “I don’t like this because…”

- My focus at this point is on the overall story, not so much on grammar and that kind of thing, but feel free to include comments of that nature if you’d like.

I also LOVE hearing what you enjoy as you read: sentences, characters, bits of dialogue, sections where you couldn’t stop reading, plot twists that you didn’t see coming but that landed just right. It is super encouraging to hear what I did well in addition to what I need to work on.

Questions you can keep in mind while reading:

- Did the opening scene capture your attention? Why or why not?

- Did you notice any inconsistencies in setting, timeline or characters? If so, where?

- Were there places where the pacing was too slow or too fast?

- Were there things that confused you? (word-usage, information reveals, action sequences, character motivations, etc)

- Did the dialogue keep your interest and sound natural to you?

- Was the ending satisfying and believable?

- Plus anything else you’d like to tell me!

Once you are done reading, please let me know as soon as possible! That way the story will still be fresh on your mind. Please send me your comments and set up a call so we can have a quick chat and I can ask you additional questions about your reading experience.

Questions? Concerns? Let me know!

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate your willingness to read this draft and help me make it better.

Thank you!

Yvonne

Example Follow-Up Messages

Hi Jay!

How are you doing? How is the reading coming along? I’d love to get your feedback or comments soon :).

Cheers,

Yvonne

Hi Yvonne,

I hope you are doing well! I am still reading your book, can I get it back to you in another week?

Jay

Hi Jay,

Thanks for getting back to me and for your comments! They are very helpful :).

Could we possibly schedule a video call sometime next week? It’d be great to pick your brain a little more.

Let me know a few times that work for you!

Yvonne

Remember to Thank Your Readers!

Whether you pay your beta readers or find volunteers, remember to thank them for reading your manuscript. This is especially true if they read the book for free. They’ve just spent hours reading a rough version of your book. That is a huge gift!

Tell them how much you appreciate the time they spent and the feedback they gave you. Tell them the impact it’s had on you and on your editing process. If appropriate, include them in the acknowledgement of your books.

Thank them even if they gave you feedback you didn’t like. Do not defend yourself. Do not expect to agree with all the feedback a reader gives you. They still put in time and they did you a favor. Be polite. Be gracious. Remember that not all readers are going to love your book. Sit with the comments. Some won’t ring true. Others will, but painfully.

Check out my article on how to evaluate and implement feedback. Many of the points will apply to beta readers too.

Look For Patterns in Their Feedback

What if you have multiple beta readers and they disagree dramatically?

Look for patterns. If one reader hates men with beards, and another loves them, you can probably figure this is a subjective comment you can disregard. But if all your readers are confused by your character’s motivations, or by a particular action sequence in Act 2, pay attention. This is an area that needs work.

See how I did this in action after my first developmental edit.

3. Buddy up: Critique Partners & Writing Groups

Another great way to save on editing costs and build community is to join writing groups, find critique partners, and join write-in/coworking sessions.

I join multiple write-in/coworking sessions with other writers every week. This is a great way to chat, get work done, ask for help, and get an extra boost of motivation to focus, write, and edit your work.

Twice a month, my critique partner and I swap 2000 works of each others manuscripts, leave feedback, and meet in a 40-minute Zoom call to discuss the feedback, ask for clarification, and brainstorm ideas. This time has helped me further polish my manuscript.

Buddying up with other writers for critique sessions can also be a huge help in refining your book.

How to Find Writing Groups and a Critique Partner

I found my writing group and one of my critique partners through the community discussion forums at Daniel David Wallace’s Escape the Plot Forest summit.

He hosts two summits every year, and offers both paid and free passes. These summits are great places to connect with other writers in your genre, find writing groups, and improve your craft while you’re at it.

I also found another writing group later on through the summits and join coworking sessions as often as I can. I hope to eventually join the critique group in that writing group as well.

What to Look For

Again, I recommend finding other writers who read and enjoy your genre. Focus on giving kind, encouraging, and helpful critique, and ask for the same in return. Remember, you aren’t obligated to make any of the changes they suggest, but it is worthwhile to consider their critiques carefully. Usually, it’s best to have more than one person giving you feedback so you have multiple perspectives.

How to Weigh Feedback

If you agree with a critique partner’s assessment of someone else’s book, that is an indication to weigh their critique of your work more highly. If you never agree with someone’s critique of another person’s work, weigh their critique of your work less highly.

Cons of Critique Sessions

It could take a long time to get through your book. I meet with my critique partners twice a month to look at 2000 words. At that rate, it will take over two years to get through my manuscript.

However, some writing groups move much faster and can look at bigger chunks of a manuscript at a time.

4. Improve Your Craft Through Free & Cheap Resources

The more you can study the craft, the more you can apply those techniques to your writing and continue to improve. After I’d written my first few drafts of my novel, I realized that I still needed to learn a lot about story structure, character arcs, when and where to reveal information, and how to write sentences that served the reader rather than sounding pretty but leaving the reader confused.

Craft resources have made a massive difference for me, not only in editing my manuscript, but in improving my writing going forward.

There are myriad resources out there, so many that it’s easy to get lost.

Here are a few things you shouldn’t do!

- Don’t use studying the craft as an excuse not to write or edit.

- Don’t try to apply multiple structure/plotting techniques to the same manuscript. Pick one that appeals to you and stick with it!

- Don’t get stuck endlessly editing your book.

- Don’t let yourself get demoralized by how much you need to learn.

Since this post is all about how to save money, I’ll mainly focus on free or relatively economical resources.

Attend Writing Summits

I’ve loved attending Daniel David Wallace’s summits, so much so that I know put them on my calendar every year.

The all-access pass is quite reasonable, especially if you get his email newsletter and nab his early-bird discount. But if the all-access pass is still too much, you can also attend on the free ticket. On the free ticket, you’ll have 24 hours to watch each speaker after they air.

His summits are Escape the Plot Forest, usually held in October, and Perfect Your Process, usually held in March.

Other summits to consider include:

The Resilient Writers Book Finishers Summit

Worldshift Speculative Fiction Writer’s Summit

HearthCon: The Cozy Fantasy Writer’s Convention

Writing Romantasy Mastery Summit

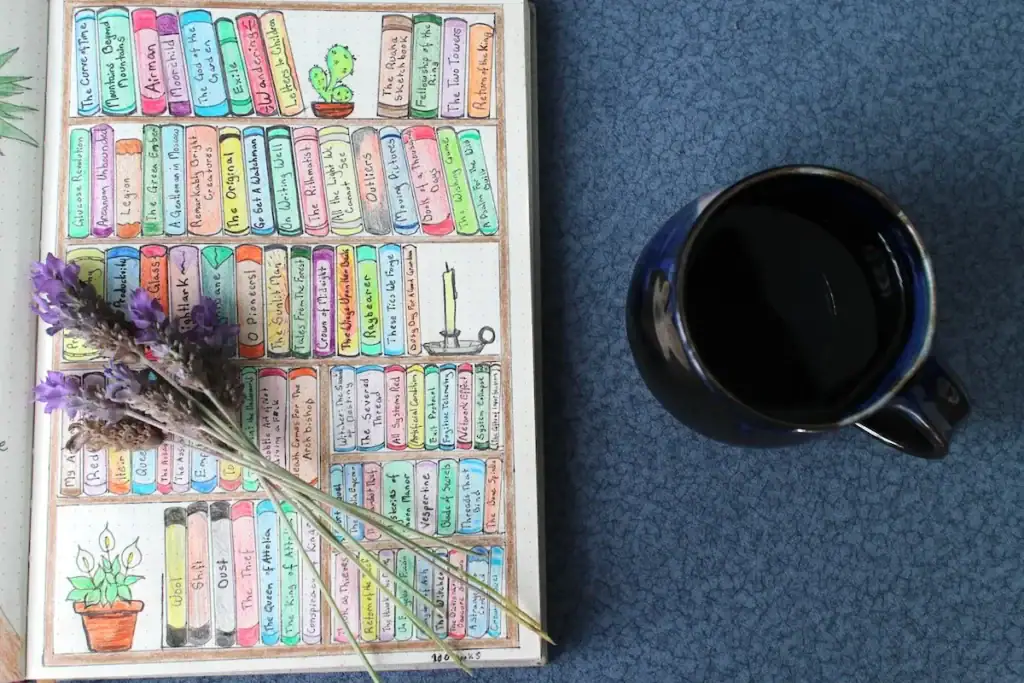

Read Craft Books

Books about craft abound! Some of my favorites include:

Conflict & Suspense by James Scott Bell

It’s high time I re-read this book, but it made a big impact on my writing and helped my craft the most suspenseful version of my first plot point in my first young adult fantasy novel.

Seven Drafts by Allison K. Williams

Williams offers a fantastic resource on how to revise a manuscript in seven drafts, with each draft focusing on a different aspect of the novel: plot/story, character, technical, etc.

Books about writing and creativity in general that I’ve found helpful and inspiring:

The Artist Way by Julie Cameron

If you’ve ever felt creatively blocked, this book by Julie Cameron is considered the seminal work on creativity for a reason. It has made a big impact on my creative life and helped me face many of the fears and creative wounds that have held me back in writing and sharing my work with the world. I highly recommend it.

Me Before You: Confessions of a Comma Queen by Mary Norris

If you shrink in terror from punctuation, worry about how to use commas and semi colons, this light-hearded and fun part-memoir will help you approach grammar in a whole new way.

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

This book is a beautiful foray into why we write and the difference it makes.

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

If you are looking for a hilarious, self-deprecating, and wonderfully honest guide to the writing life, with all of its vulnerabilities, I can’t recommend this book enough!

On Writing Well by William Zinsser

Zinsser’s book is both a kick in the pants and an inspiration. It was a wonderful reminder to write concisely and boldly, to think clearly, and to explore the world of words with audacity and precision.

Read Blogs about Writing Craft

There are millions of resources available online, so many that it can get overwhelming. However, here are a few websites I’ve found especially helpful and inspiring, and which helped me learn more writing craft.

K.M. Weiland’s website Helping Writers Become Authors was one of the first writing blogs I used, and it helped me make massive strides in understanding story structure.

I’ve also been a subscriber for many years to Anne R. Allen’s blog on writing. Her posts about dialogue are ones I’ve referred to and sent many of my clients to as well.

Sign up to Email Newsletters

Email newsletters I’ve found especially helpful in my writing journey include:

Daniel David Wallace offers a unique and thoughtful approach to writing craft that I’ve found impactful and inspiring. I love his teaching style and have purchased many of his courses. However, even if you can’t afford a course yet, consider getting on his email list!

Gabriela Pereira’s DIY MFA newsletter is also chock-full of helpful resources, interesting approaches to writing, deep dives into story and plot, and more.

Although I’m somewhat new to her list, I’ve found Allison K Williams’ emails especially helpful, especially her Draft to Done free email course.

5. Hire an Editor to Look at Portions of Your Work

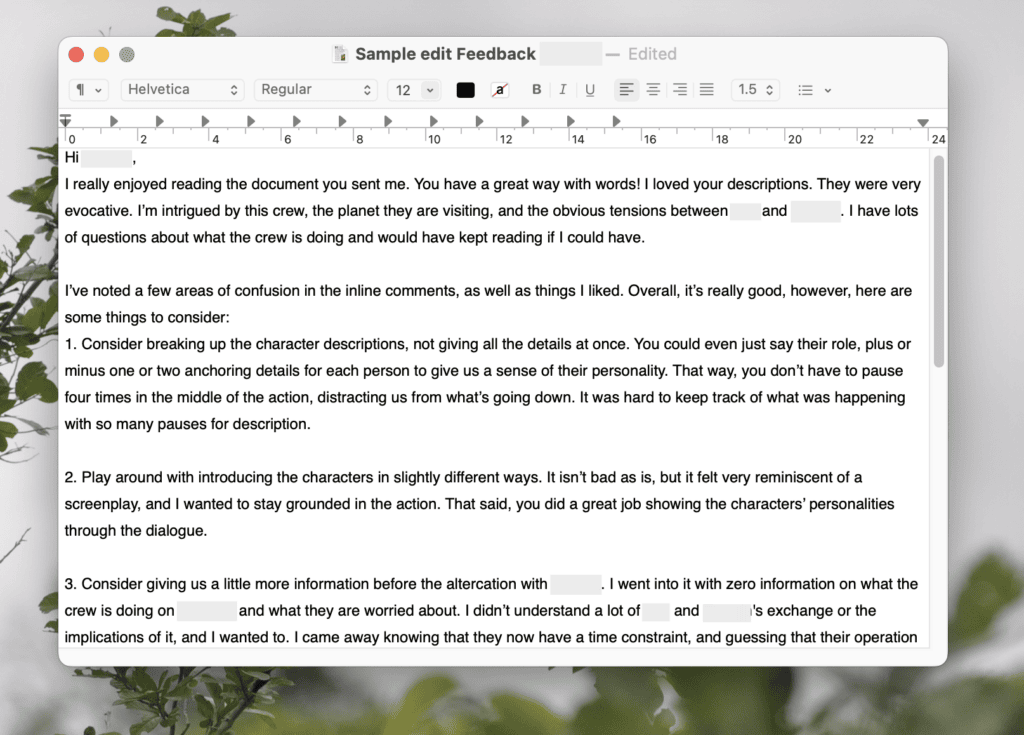

If you can’t afford a full developmental edit, you may still want to get professional eyes on a portion of your book. Although this won’t help you identify major structural issues, you can often extrapolate the feedback from a small section (for example, the first three chapters) and apply it to the rest of the book.

Why? Because most of us commit similar errors across the board. In my first book, my overuse of metaphorical language was evident from the beginning.

Often, I can offer advice on dialogue, interiority, beginnings, and use of language from a section of a manuscript.

What I can’t tell is where the structure might break down, places where the pacing is too fast or too slow, how effectively the character arc works over the course of the novel, and other big-picture things like that.

Some exercises that can help you check these larger structural issues include writing a logline, query letter, and synopsis. Being forced to condense your book into 750 words, 500 words, three paragraphs, and one sentence means that you must be very clear on what the story is, on the promise, progression, and payoff, and the through-line.

Interested in hiring an editor for at least a portion of your work? Follow my suggestions for finding an editor great for you.

6. Use AI Editing Tools

Some writers find AI editing tools very helpful and cost effective.

AI editing tools can be used at any stage of the process from larger structural editing to line editing to an initial copy edit. For example, I use a combination of Grammarly and ProWritingAid to catch errors in my work before passing my draft on to beta readers.

Other writers use AI tools like AutoCrit or Ana del Valle’s AI Creative Writing Academy to help them identify a range of problems from structural to pacing issues to catching clichés.

Remember: these tools should supplement and support your writing process. They shouldn’t replace human feedback. Consider AI feedback with a critical eye and don’t implement it wholesale.

Only use AI tools that have been specifically trained to do the task you are asking them to do.

I don’t recommend using ChatGPT for writing advice unless you use a custom GPT trained to a specific purpose, like the tools mentioned above, or those trained by writing teachers like Daniel David Wallace. At minimum, ask yourself the same questions you would if a human gave you that feedback.

The more you know about craft, grammar, and style, the more discerning you can be when it comes to evaluating AI feedback.

7. Lock in Your Mindset

Self-editing goes hand in hand with learning and improving your craft, while alpha and beta readers and critique partners can help point out areas that you still need to work on. Craft books, summit talks, and blog posts can help you learn helpful techniques you can apply to editing your manuscript.

It’s a loop: self-edit, get feedback, self-edit again.

As time goes on, you’ll get better at recognizing weak areas and fixing them before getting feedback, you’ll also get better at evaluating the feedback you receive and deciding how to implement it. And you’ll find the people who get you, your writing, and offer the most helpful critiques, helping you optimize the process.

Developmental editors can be a crucial part of your journey, but even once you’ve gotten your book into good enough shape and saved enough to hire an editor, there are important things to know going in.

You need the right mindset.